Thomas Fetterman

He learned how to stay positive in the face of adversity.

Based on the 2023 interview with Meredith Sellers from the Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians, Philadelphia.

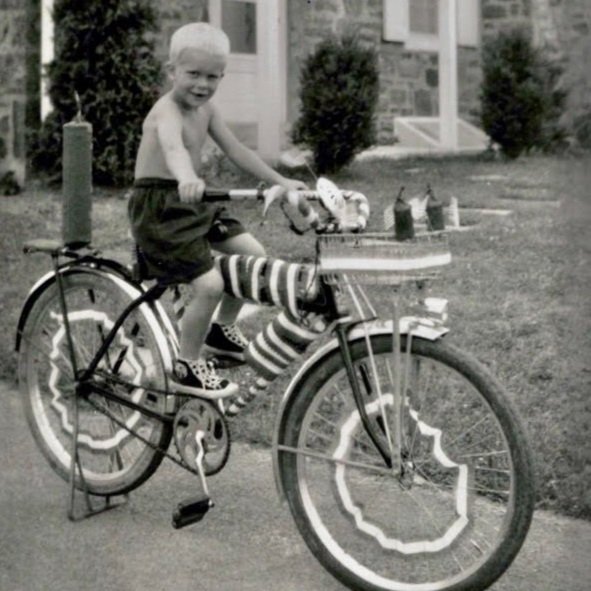

It was 1953, Tom was eight. “I was running races in the schoolyard with friends, and I kept on falling down. I had a bad headache and went to the nurse. My mom picked me up and took me home. Every time I lifted my head up in bed, it hurt like the devil.” The family doctor came out to the house and he thought I had what they called “grip”, which was a kind of viral cold. It got worse and worse and I began having breathing issues and pain in my body so they took me to Hahnemann Hospital in Center City, Philadelphia. They didn't really know what I had and I was put in a children's ward. They thought I had spinal meningitis and gave me a spinal tap, but it wasn't definitive. They started giving me these “big honker” penicillin shots every two hours, day and night, for two weeks (to this day, I'm not very fond of injections). I knew something was wrong. I was very thirsty so I climbed out of bed and my legs just crumpled underneath me. I ended up on the floor and stayed there until they did their rounds and found me. Then they finally got the diagnosis, I had polio.

They sent me off to an isolation ward in Montgomery Hospital where put me in a glass room. I was laid on what was nothing more than a stretcher. It seemed as though my whole body had rigor mortis - I was completely stiff - like a board. I couldn’t lift my head up, I couldn't move my arms, legs. Nothing. I was only eight and I lay there thinking "What the heck is this?" It was worrisome and deep down I thought something serious was going on. My parents came, but they were not allowed in. They had to stand outside in a gown and look at me through a window. Everything that I owned was burned. All my clothes, all my books, and all my toys, including my prize Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett coonskin hat. I guess now I would call it “traveling light” but then, it was awful. After couple of weeks, I was no longer contagious. I was moved to Sacred Heart Hospital in Norristown, which is a Catholic hospital where nuns were the nurses. I was not a Catholic and hadn’t ever interacted with nuns. It turned out they were terrific and they took very good care of us all.

My body was still very rigid and I was still having trouble breathing. That's when they put me in an iron lung. I remember even without any activity, I was short of breath. Just laying there, I’d be short of breath. I remember that big machine being soothing because it just pushed and pulled . . . pushed and pulled . . . pushed and pulled having it’s own special rhythm. It was actually relaxing, a little hypnotic, and once you got used to that sucking and blowing sound, it was calming and reassuring. I would think to myself “Thomas, you’re still breathing and that's a good thing.” Inside the iron lung next to me was a lovely adult woman. She had three small children. As we lay there, with our heads sticking out, we could both speak. She was very maternal toward me, which was quite amazing. She was in there the whole three months that I was there. Her husband and her three kids, little toddlers, would come every day and she would look at them through the mirror above her and talk to them. Even with the positive memories, it was frightening. I’m glad I was only in there for a short time.

After couple of weeks, they finally moved me out of the iron lung. By that time, I could move my head and I could move my arms a little. I I was quite worried about what was going on with my body. I was in a room with another boy - Wesley Davis. He and I were about the same age and we became quite good friends.

Rocker Bed. Photo courtesy of Michael Alexander, MD, Thomas Jefferson University

I did better in the iron lung than I did on the rocker bed – it was a bed that I just was strapped onto. It would very slowly go back and forth and push the weight and lift the weight off the diaphragm. This eight year old thought it rocked on and on for way too long. It was supposed to help me sleep, but I had a hard time sleeping and was not relaxed at all. They had these draw shades that came down and covered the complete window. I remember that it wasn’t until I saw the little crack of light at the very bottom, when I knew the sun was coming up, that “bam, I was asleep”. I could finally relax for a minute. It wasn’t dark, “I'm not afraid. I'm just going to take a little nap . . . for a while.”

I wasn't in the iron lung 24/7. I was taken out and my body was moved and stretched by the therapists. I was treated with the Sister Kenny method, where the therapist put very hot, wool pads around my arms and legs. Then once they got you warmed up, Ms. Van Horn would come in. A lovely woman, she was a very sweet, but no-nonsense person. She would stretch me . . . really stretch me. She'd put you into these horribly painful positions. One thing I remember clearly, was everybody screaming out because it hurt so much. She would do it to one child at a time as she moved down the hallway.

“Many hours of exercise and skilled care are needed to help Tommy Fetterman, in his fight against polio.” “The training of physical therapists and physicians is part of a large program paid for by the March of Dimes Funds. The drive to fight polio is on.” Source: The Herald

My muscles were stiff, like a board. I remember they had this thing with blankets, that had hot pads in it. They’d go room to room, plugging them in. You'd lay there and hear this progression of screams getting closer and closer and closer until it was your turn to scream. But, it limbered up my joints, and very, very slowly, they made me bend a little bit further each day. It worked. We all became much more limber and that was great. It gave us more mobility, and with more mobility, we had a lot more fun.

Wesley and I would go up in the elevator and feed the monkeys they had in the science department. They took us on trips. We got to go to the local zoo and we started swimming therapy at the Norristown YMCA. We became like a family. I was lucky to have people around me in the same situation; we shared everything, and I think that made it easier on everybody, at least it did for me.

The nuns made a leg brace for me. Then they gave me wooden Kenny armband crutches. They took me into the rehab room with gym mats on the floor. The therapist would get me walking around and around the mats doing all kinds of maneuvers. After I got pretty good at it, they would sneak up behind me, kick a crutch out from underneath me, and watch me fall to the ground. This is how they taught me how to fall. As hard as it was, I’m glad for the lesson - I've probably fallen more than 500 times in my life. If I hadn’t learned how to fall, I’d be in really bad shape.

My Mom and Dad were absolute troopers. They lived forty-five minutes away and visited me every single day for the whole time I was in Sacred Heart Hospital. One day, they had not one, but two flat tires, and there was no spare. They called and said, “We are so sorry, we can't make it." I didn’t mind. I have a wonderful family, and they were very, very caring. I have two brothers who visited along with friends that my Mom would drag along.

And for me, it was my first traveling experience and my first experience away from home. Initially, I was afraid, but after I got a hold of what was going on I realized that I was meeting wonderful, supportive people. The parents that came to visit their children were wonderful, and they would visit everybody. It was quite amazing. At the same time, my community where I grew up was very generous. They would send me special cards - a train that had dimes in the wheels, and one that had quarters in the engine. They built a little HO train track for me for me, so I could play in my bed. I look back and realize what a gift it was. Perhaps it was because given the number of children who got polio, I could have been any one of their children. At only eight, I realized I had to be heroic, even though I didn't feel so. They wanted me to have a stiff upper lip, they wanted me to be a smiling little guy who appeared to believe "I'll be all right, don't worry about me." So, I rose to the occasion. That has served me well, as I was, and continue to be, upbeat and personable.

When they burned everything, that included my Daniel Boone Davy Crockett coonskin hat. In 1953, that was the big rage, Davy Crockett (played by Fess Parker) was on everything. Some years ago, I sold a patent of mine to a medical company, and they wanted me to come to Santa Barbara, California to demonstrate it. Santa Barbara was where Fess Parker owned a business. I saw him walking into the hotel. I walked up next to him and I started singing one of his songs as he walked by. He stopped and finished the song. We sat down and we talked, and I told him about the polio and the coonskin cap. Shortly after I got home, I got a box, and it had a coonskin cap, signed by Fess Parker - Daniel Boone. It was a sweet ending to a lovely experience.

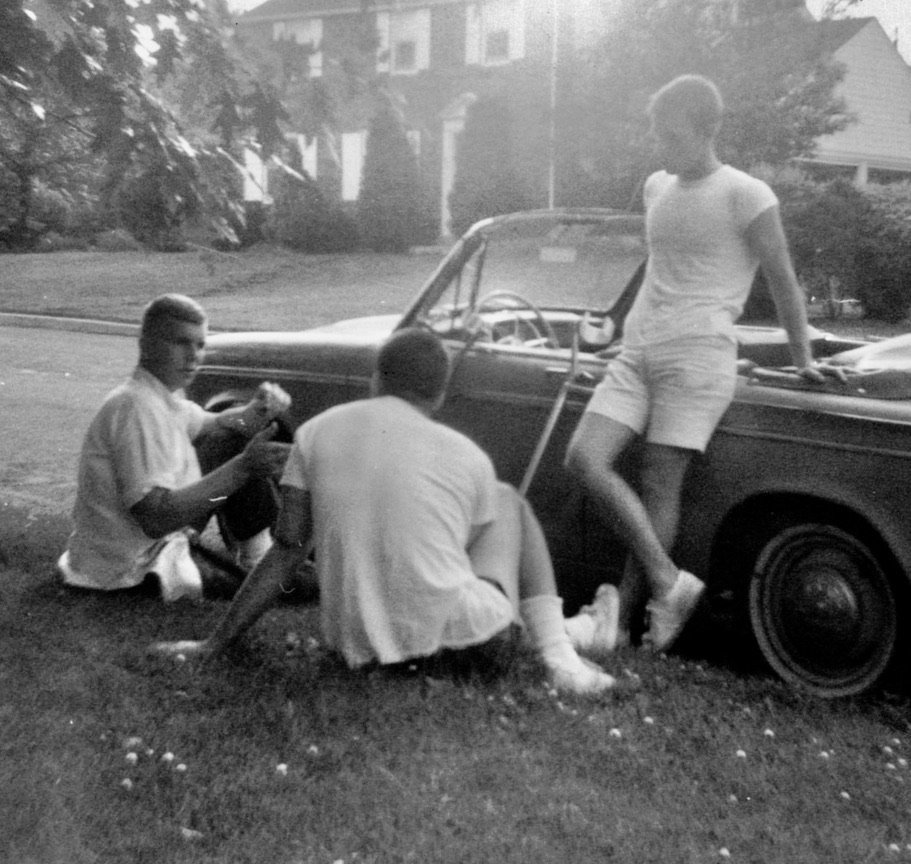

I missed three months of school. When I was ready, they let me go back to my class. They thought it was important that I stay with my peers. To this day, I can't read Roman numerals. I missed that. Of course, the schools were not at all handicap accessible. With all I had learned, I had never been taught how to go up and down stairs. I remember being in class and realizing that the next class was upstairs. The teachers were kind and let me out five minutes early from class so I could struggle up those steps. In the beginning, I went up on my butt. I sat down on the second step, and then I pushed myself up and pushed the crutches up a step and on to the next one. Within a week, I was walking up and down steps. After a couple of months, my upper body kicked in. I started developing muscles in my upper body while I was doing two steps at a time on my crutches. I wanted to stay up with the other kids. I still have a lot of those friends and that’s a good thing.

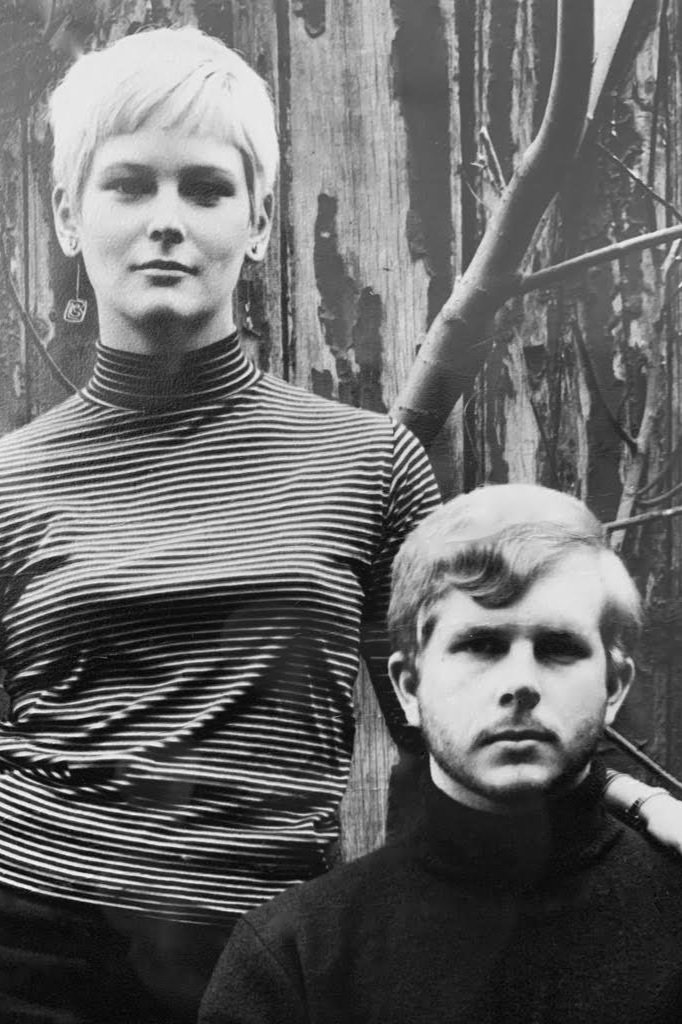

I was only eight when I realized how fragile life could be. Now, I look back on my life with a disability. Next to my lovely wife and daughter, and now granddaughter, polio was one of the best things that ever happened to me. It drew me out, it gave me a very optimistic feeling about people, and also a great sense of adventure. I was no longer afraid.

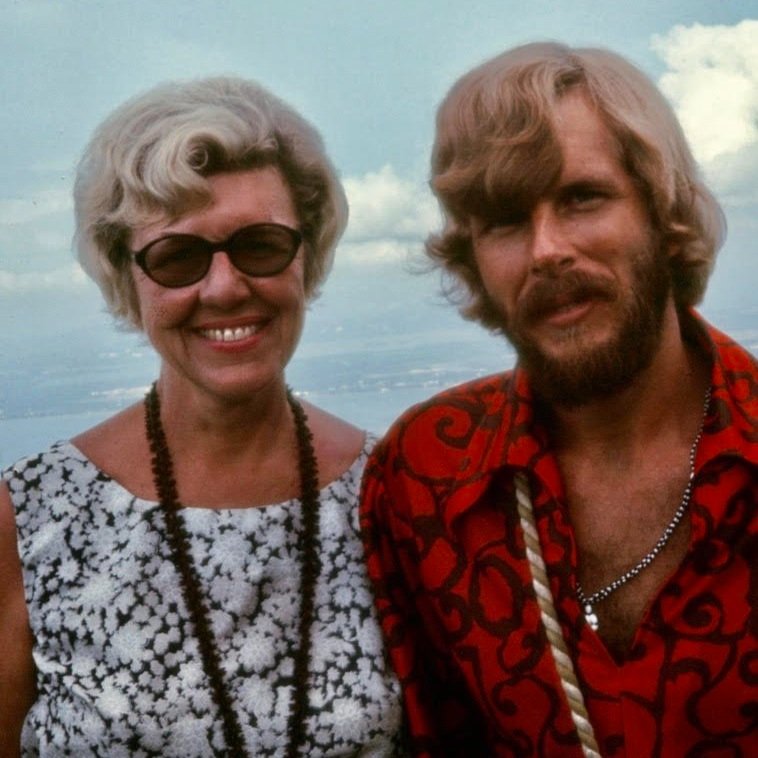

When I was 18 or 19, I realized that my mobility would always be limited. I was strong. I knew I wasn’t going to be strong forever and wanted to really live. My wife Cate and I have lived all over the world - in India, Bali, Indonesia, and Greece. We've been around the world four times. I've climbed Borobudur, and I've climbed up to the Acropolis twice. Back in the 70s, I went overland from Germany to India, spending six months on the road. I don't think I would've done any of that if I hadn't had polio.

I do remember when the polio vaccine came out in the sugar cube. I would have been 15 and in Junior High. I remember asking the doctor, "What are the chances of me getting polio again?" "Oh," he said, "Probably one in a million." My response? "Give me that sugar cube." I got vaccinated. I wasn't going to take any chances – and never wanted to go through it again.

Since 1988, I’ve been working with people with every possible kind of disability. As a result of my struggling with shoulder pain from having used crutches since I was 8, I invented and patented a new crutch tip technology with a built-in shock-absorbing system. Regardless of where in the world we live, disabled people are the most amazing people I’ve ever met. It's just remarkable to me how people thrive under adversity.

Unless noted, photos provided by Thomas Fetterman.

Thomas’s company - Fetterman Crutches was inspired by his own disability.

Thank you Meredith Sellers and the Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians, Philadelphia

for your inspiring video about Thomas’s life. Staying Positive in the Face of Adversity - My Time Inside an Iron Lung