African Americans, Polio, and Racial Segregation

Many physicians in the early twentieth century believed that African-Americans were less susceptible to polio, or infantile paralysis as it was then called. They came to this conclusion because they saw fewer Black patients in their practices. Later work by scientists and historians has determined that black people were about equally susceptible to polio as whites, and that the differences noted by physicians at the time had more to do with the impact of Jim Crow segregation rather than some biological difference in susceptibility. Before World War II most African-Americans lived in the Jim Crow South where there were fewer polio epidemics. Most polio epidemics in these years occurred in the Northeast and the Midwest which were overwhelmingly white. In addition, because of segregated medical practices and facilities, black people were less likely to be treated and much less likely to be treated by white doctors engaged in polio research. There were relatively few Black physicians in this era and almost none participating in polio research.

Margaret Bourke-White: Unpublished Photo from the Warm Spring series, 1938.

The medical historian Naomi Rogers noted that in the 1930s the neglect of Black polio patients became “publicly visible and politically embarrassing.” Few facilities in the segregated nation treated Black patients and few Black physicians and physical therapists were available to provide treatment. The result was that most Black polio patients received no care or substandard care. This situation became politically embarrassing in connection with the polio rehabilitation center Franklin D. Roosevelt had established in Warm Springs, Georgia, in the heart of the Jim Crow South. Although African-Americans contributed substantial funds to the President’s Birthday Ball campaigns that funded Warm Springs, they were not admitted as patients to the facility. During and after Roosevelt’s 1936 campaign for re-election, Black leaders publicly protested this injustice.

White Guests and Black Waiters at Warm Springs Dining Room, Circa 1950 Source: March of Dimes Archives, White Plains, NY

According to letters in the Roosevelt Library from Basil O’Connor, the head of the March of Dimes, to President Roosevelt, O’Connor took up the issues of black exclusion from Warm Springs in the Spring of 1937. After soliciting advice from the Warm Springs Board of Trustees and from Henry Hooper, the administrator of Warm Springs, O’Connor informed the President the facility did not and would not admit black people as patients, In the mid-1930s all of the patients, medical staff, and administrators at Warm Springs were white. However, 43 of the 93 employees were African-American. The Black employees were restricted to service roles such as maids, waiters, push boys (who moved patients around the facility), laundry workers, janitors, and groundskeepers. A letter from Henry Hooper to O’Connor put the case against Black patients at Warm Springs. Hooper assumed that to admit Black patients would require Warm Springs to maintain racial segregation. Accordingly, admitting Black patients would require building a separate cottage to house 8-10 patients and a separate pool in which they could receive the hydrotherapy that was key to the Warm Springs treatment. A separate pool alone would cost some $3,000 ($53,000 in 2020). They would also require separate African-American staff including a graduate nurse, an attendant, a physical therapist, an automobile driver, a maid, and a cook. Hooper also noted that Black graduate nurses and physical therapists were almost nonexistent. Other factors arguing against Black admissions included the fact that many Black patients had received inadequate care in the early stages of their illness and thus were unlikely to benefit from the kinds of therapy that Warm Springs offered. Hooper also worried that poor Black families would be unable to provide proper care after patients were discharged from Warm Springs. Finally, there was the matter of cost. Warm Springs patients were expected to pay for their care and Hooper argued that most Black families would be unable to pay for their child’s care at Warm Springs. He assumed that most would be charity cases and Warm Springs would have to assume the cost. He estimated that caring for 8 patients a year would cost the facility about $18,000 ($320,000 in 2020). Such a sum would only add to the annual deficit and detract from the already existing programs for white patients. Hooper suggested that a better solution would be for the March of Dimes to establish a segregated rehabilitation facility for black people at a Black institution.

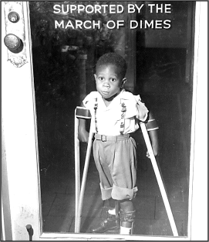

James Clark Allen, March of Dimes poster child, 1955. Courtesy of March of Dimes

In passing Hooper’s recommendations to the President, O’Connor commented that it was his understanding that black people were less susceptible to the disease than whites, implying that they thus needed less care. He also complained that the objections to the absence of Black patients at Warm Springs came largely from what he called “professional colored promoters” and “sob-sisters connected with institutions such as Teachers College at Columbia University.” In another letter to the President, O’Connor endorsed Hooper’s suggestion of establishing “relations with an institution already equipped for the care of colored people.”

In 1939, the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis supplied funding for a center at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, where black patients could go for treatment.

Courtesy of March of Dimes and National Museum of American History

To his credit, O’Connor did move relatively quickly to provide funds for a facility to treat Black polio patients with the most up to date methods. In 1939 he announced that the March of Dimes would provide $161,350 ($2,864,000 in 2020) to create a modern rehabilitation facility for black people at the nearby Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. This was a college and trade school for African-Americans established by Booker T. Washington following the Civil War and the end of slavery. This facility would provide care for Black patients as well as training in polio treatment for Black physicians, nurses, and physical therapists. The Tuskegee facility opened in January 1941. Once opened, it clearly provided the best polio care available to Black patients in the segregated South, but the overall number of patients treated there was relatively small. For one thing, it was difficult for many Black families to transport their children long distances to Tuskegee and to pay for their care once there. In an interesting side note, O’Connor in the 1940s became president of the Tuskegee Institute Board of Trustees.

An exception to the segregation of polio treatment in the South occurred in Texas. Texas generally practiced racial segregation, but somewhat less rigidly than other states. In 1941 citizens and physicians in Gonzales, Texas, east of San Antonio, established a polio rehabilitation facility modeled on the Georgia Warm Springs facility which they called the Gonzales Warm Springs Foundation. Unlike their Georgia counterpart, the Gonzales facility admitted white, black, and Latino patients equally. According to historian Heather Wooten, the Gonzales institution was the only racially integrated rehabilitation in the nation at its founding. At least two other Texas institutions that treated polio patients in the 1940s were also racially integrated. The Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Crippled Children in Dallas and the Jefferson Davis Hospital in Houston had integrated polio wards for children. Ironically, the Jefferson Davis Hospital was named for the president of the Confederacy. When the March of Dimes established the Southwestern Poliomyelitis Respiratory Center at Jefferson Davis Hospital in 1950 it admitted polio Black, White, and Latino patients, adults as well as children. These centers were established across the nation to centralize the treatment of polio patients in iron lungs and were the precursors of intensive care units. Wooten speculates that Texas was more accepting of racially integrated polio facilities because of the complex racial mixture of White, Black, and Latino in the state and because the facilities were not tied to the political fortunes of a president who needed the support of racist Southern white Democrats.

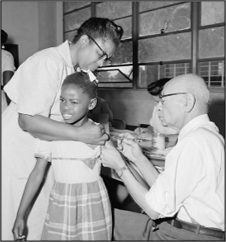

The rigid racial segregation of polio patients began to break down during the 1940s. During the massive 1944 polio epidemic in Hickory, North Carolina, the March of Dimes established a polio hospital that was racially integrated. By 1945 at least some Black children were being treated at Warm Springs. In the mid-1940s, the March of Dimes hired an African-American, Charles H. Bynum, to coordinate the organization’s inter-racial activities. Bynum pushed the organization to include black people not only on the fundraising side, but also to ensure that they had access to the treatments funded by the March of Dimes. When the March of Dimes supported the 1954 trial of the Salk polio vaccine, Black children were included in the trial. However, there were still inequalities. In some Southern cities where the Salk shots were given in school auditoriums, black children were forced to take their shots on the front lawn since they were not allowed into the white school buildings. Black people were also included in the Sabin vaccine campaigns in the early 1960s.

A second grade girl receives a poliomyelitis vaccination during the 1954 field trial in Laurel, MS

Source: Winifred Moncrief Photo Collection

Although it is clear that polio was no respecter of artificial racial distinctions, it is also clear that African-American children and adults who contracted polio in the first half to the twentieth century received inferior care in both the acute and rehabilitative phases of their disease. Black hospitals were almost always inferior in both the facility itself and in the physicians and nurses who provided the care. There were simply not enough well-trained Black medical personnel to provide the necessary care. Black polio patients in northern cities were more likely to receive better care, but even here they might be confined to segregated wards in white hospitals. The situation began to improve only when Black leaders and physicians publicized the inequities and embarrassed the March of Dimes, which provided much of the funding for polio care and treatment from 1940 to 1955, into moving to provide access to up to date care and treatment.

March of Dimes official Charles H. Bynum accepting a check from MR.s J.A. Jackson, secretary of the Grand Chapter of the Order of the Eastern Start of Virginia, December 3, 1955.

Source: Afro-American Newspaper Archives and Research Center, Baltimore, MD

Note on Sources:

The Basil O’Connor letters to President Roosevelt are in the Roosevelt Presidential Library in Hyde Park, New York.

On Georgia Warm Springs, see Naomi Rogers, “Race and the Politics of Polio: Warm Springs, Tuskegee, and the March of Dimes, American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 97, No. 5, May 2007 (The article is available through Google at Tuskegee polio.).

For polio in Texas see, Heather Green Wooten, Polio Years in Texas: Battling a Terrifying Unknown, Texas A & M University Press, 2009.