Painting Light in Polio’s Shadow: One Artist’s Struggles

A Book Review by Pamela Sergey

Survivor Sharon (White) Richardson

A passionate landscape painter, Sharon (White) Richardson writes about her own struggles with post-polio syndrome (PPS) in her memoir Painting Light in Polio’s Shadow: One Artist’s Struggles. On her website (www.sharonrichardson.net), Richardson expands “Most books about polio survivors focus on the direct effects of the crippling disease. Mine deals exclusively with Post-Polio syndrome (PPS) – the new muscle weakness, pain, and loss of control - that occur years after surviving the polio virus (56 years for me), and the drastic effects it had on my career as an artist.”

The book is a triumph of acceptance, adjustment, determination, and persistence crucial in overcoming adversity. Richardson writes in great detail about the physical and mental obstacles that she worked through while struggling with her PPS during the last 20 years, and the many successful work-arounds she invented to continue painting despite PPS. She continues to live by the wisdom she found in a fortune cookie and taped to her easel: "Don't let what you can't do get in the way of what you can do.”

In a personal email to this author, Richardson adds: “My hope is that once the reader has accepted their physical loss (a difficult and often lengthy process) and is searching for ways to adjust and adapt to their new situation, something in the book about my particular experiences will spark a "what if" idea that is applicable to their situation. Rather than acquiescing to defeat from not being able to do something they are passionate about and truly enjoy, they can visualize a way around the obstacles they face or even explore doing something new that is similar and just as satisfying.“

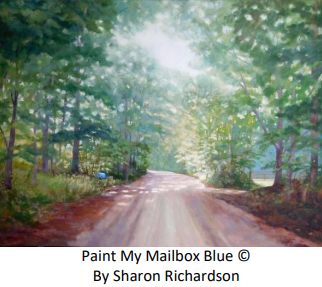

A sixth generation Mississippian and descendent of the founders of Natchez, her current hometown, Richardson enjoys painting the lightfilled Southwest Mississippi landscape. A daughter of an artist, she graduated from the University of Georgia with a BS in entomology, but it wasn’t until after graduation that Richardson took her first oil painting class. Since then, she has studied plein-air landscape painting (the practice of painting landscape pictures out-of-doors) and pastel portrait painting, with numerous accomplished artists. In her personal artist statement she admits “The way that light and the resulting shadows magically transform the dullest, most uninteresting subject into one full of excitement and charm has always fascinated me. Almost anything can be beautiful to paint if it is seen in a pleasing light. This illusive light and shadow design flowing across a landscape or still life is the focus of my oil and pastel paintings.”

Her pastel paintings and her oil paintings have been accepted and exhibited in numerous local and regional competitions including the Degas Pastel Society in New Orleans, winning the Pastel Society of America Award for her pastel painting; and three times by the Salmagundi Club in New York for her oils. Her work is included in The Mississippi Museum of Art and The Municipal Art Gallery in Jackson, Mississippi, corporations, and private collections in the United States, Canada and Europe.

In early 1946, Richardson was diagnosed with poliomyelitis. She was 8 weeks old. After a visit to Richardson’s pediatrician and a lumbar puncture to confirm polio, her parents borrowed a car and drove one hundred miles from their home in Woodville, Mississippi to Mercy Hospital in Vicksburg, Mississippi. At the time, Mercy Hospital was designated a Regional Pediatric Polio Center and Richardson’s stay was paid by the March of Dimes. Richardson responded well to the intense “Sister Kenny” method of physical therapy treatments of hot compresses, hydrotherapy and gentle massage. After two months, she had recovered from the paralysis in her limbs and her parents were thankfully allowed to take her home. Richardson would go on to live a fulfilling life as wife, mother, avid gardener, world traveler, and ardent plein-air painter for the next 56 years, without any apparent complications from her early bout with polio.

In the summer of 2002 Richardson began experiencing muscle weakness in her arms and legs, as well as neck, jaw and tongue fatigue. She had difficulty walking and talking, and could no longer paint with her right hand. It was the onset of Post-Polio Syndrome (PPS). After seeking professional medical advice, Richardson was told that the cause of PPS is unknown, there is no diagnostic test or prescribed treatment, and no way to reverse PPS symptoms. Sharon consulted with Richard L. Bruno, HD, PhD (Director of the International Centre for Polio Education). Dr. Bruno helped her with strategies that would help her live with the disabling effects of the poliovirus.

In an article by Marny Euberg, MD published by the PA Polio Survivor’s Network, Sharon learned that she is considered an “upside - downer”. Dr. Eulberg explains “This term is based on the fact that the majority of observable weakness and atrophy in most polio survivors is in the lower part of their bodies. If a person has the reverse, with most of their weakness/atrophy in their shoulders, arms, and/or hands, it is ‘upside down’ from what is usually observed.”

Richardson’s PPS setbacks forced her to find ways to compensate “for roadblocks, and alternative solutions for dead ends.” She calls them “work-arounds”. Painting Light in Polio’s Shadow: One Artist’s Struggles describes many of these work-arounds. Sharon taught herself how to paint with her non-dominant left hand, but to do this, she had to flip the arrangement of her studio so shadows wouldn’t fall on her canvas;

She created a “jacket” made of straws and duct tape to encircle the end of her paint brush making it more comfortable to hold without adding weight;

She began painting at her easel in a seated rather than standing position;

She added a drill to her easel to easily raise and lower the height;

She painted smaller canvases and simplified her signature.

Sharon purchased voice-activated computer software allowing her to continue her journal, be more active with her online PPS support group, take online writing classes, and do online shopping.

Sharon has developed a strict routine of painting for 20 minutes followed by a 20-minute rest period when she would critique her work and plan her next painting session. This arrangement has allowed her to paint three or four hours a day. Through trial and error, she learned not to exceed her rigid schedule, or she would be unable to paint for several days due to her increased “black” pain “ . . . a burning, relentless, bottom of the barrel pain that made me feel helpless and hopeless.” Unable to paint outside during COVID, Richardson switched to the centuries old tradition of still life painting and pet portraiture. She was painting, “and that was all that mattered.”

Through her own PPS mantra “acceptance, awareness, and adjustment“ Sharon Richardson has been able to continue to share her “enthusiasm and passion for light, color, and nature with others.”

“Joyfully returning each day for new adventures at my easel, I engage my jerking arms and trembling hands. I incorporate their uncontrolled movements into my brushstrokes one spot of paint after another. Lefty paints big shapes with an amended brush, and with a regular brush, Righty paints nuances and detail. I’m grateful for this arrangement; I’m at peace painting within my bounds.”

– Sharon Richardson